The Case for Micromanaging

A Reflection on Leadership Attention, Creative Control, and Commercial Intent

Micromanagement is widely criticised in contemporary management literature. It is regarded as inefficient, unscalable, and demoralising. Many argue that it reflects a leader’s failure to delegate or to trust, and that it undermines autonomy within an organisation.

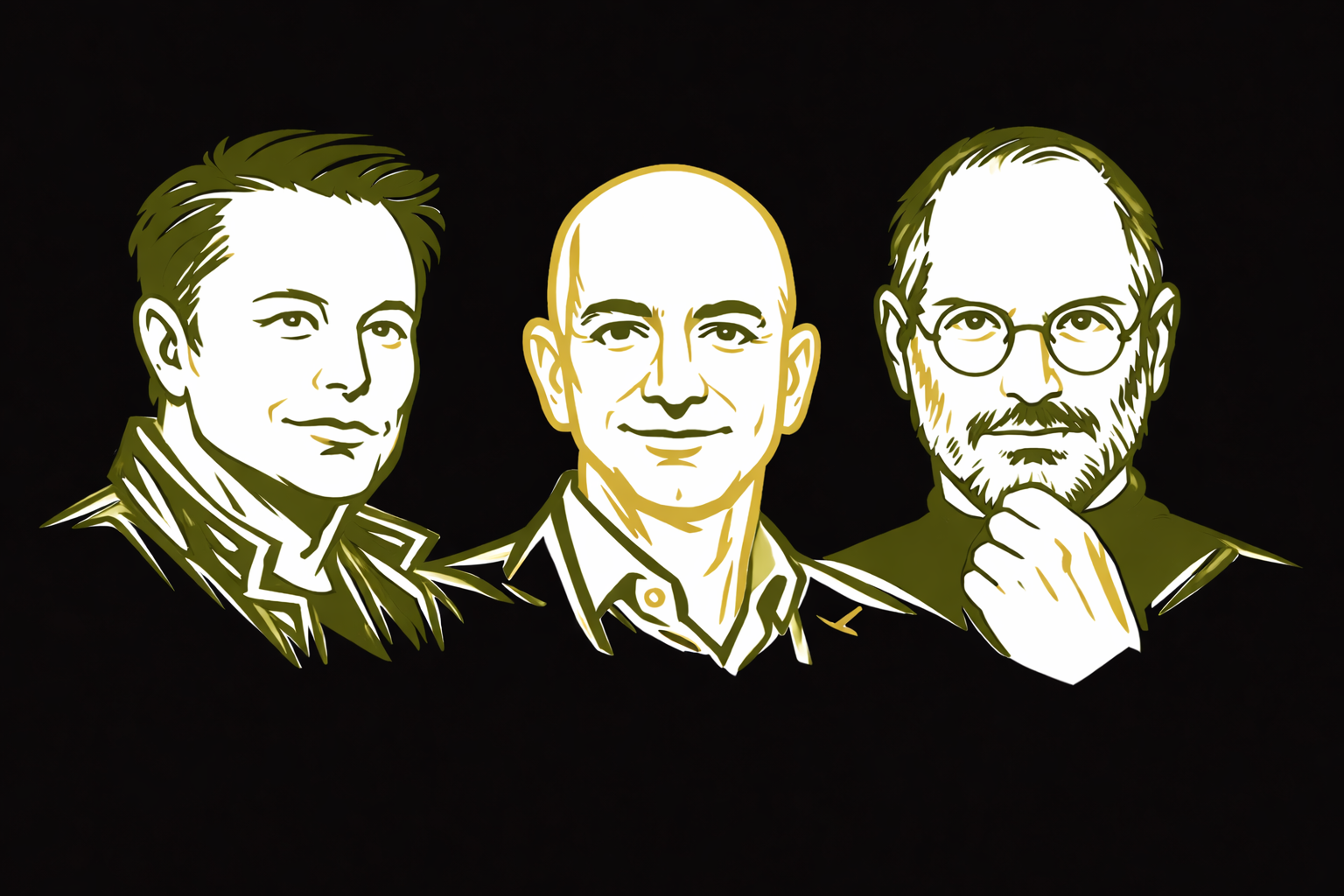

There is merit in these concerns. However, it is also true that some of the most effective business leaders in modern history have exhibited precisely this behaviour. Elon Musk, Steve Jobs, and Jeff Bezos were, and in some cases remain, highly involved in the smallest operational and creative details of their companies.

I recently read Robert Bruce Shaw’s All In: How Obsessive Leaders Achieve the Extraordinary, in which he offers extensive documentation of this trait across their careers. What emerges is not a defence of micromanagement per se, but a recognition that in certain contexts, a high level of founder involvement is not only rational, but necessary.

The relevant question is not whether micromanagement is good or bad in absolute terms. It is when, why, and how it is used. What follows are four principles that can assist in evaluating when close oversight may serve the business, the product, and the team.

Product over Power

The first principle concerns motive. Micromanagement becomes pathological when it is used to assert power, particularly in domains where the leader’s input is neither required nor constructive. However, when the behaviour is directed toward the integrity of the product or service itself, it reflects a form of stewardship.

Jeff Bezos exemplified this during the formative years of Amazon. His involvement in customer experience design, logistics, pricing mechanics, and service interfaces was not merely symbolic. He believed that customer trust was earned through precise execution, and he involved himself accordingly. This was not an attempt to dominate his organisation, but to align its actions with its intended value proposition.

Micromanagement, when directed toward the product with clarity of purpose, is not inherently dysfunctional. It becomes a way of ensuring alignment between vision and outcome.

Perfection over Production

The second principle concerns context. There is a significant distinction between products that are incremental and those that are unprecedented at the time of launch. In the former case, speed and efficiency may be the dominant commercial drivers. In the latter, the defining factor is often quality.

The original iPhone, Amazon Prime, and Tesla’s Model S were not conventional market entries. They redefined categories. In such instances, the first iteration is not just a release; it is a reference point for the entire industry. When the product is fundamentally new, the margin for error is reduced, and the role of quality increases. For leaders operating in such environments, perfectionism may not be a liability. It may be a requirement.

By contrast, when the product is commoditised, or when the differentiation is minor, the commercial return on perfectionist oversight declines. In these cases, speed of execution, cost control, and process efficiency become more significant. The founder must determine whether their proximity is adding strategic value or merely satisfying personal preference.

Proof over Promise

The third principle concerns competence. Much of the criticism of micromanagement is based on the assumption that someone else could perform the task equally well, given the opportunity. This is often true. However, in certain moments, especially in early-stage companies, the founder may in fact be the most qualified person available. They may have more context, more refined judgment, or a clearer sense of the intended outcome.

Steve Jobs routinely took control of product direction at Apple, even late in the development process. He did so because he had specific standards that were difficult to replicate through delegation alone. In doing so, he risked alienating teams. However, he also produced results that fundamentally changed the trajectory of the company. His involvement was not based on a desire to prove superiority, but on the recognition that the consequences of a misstep would be disproportionately large.

Founders must assess whether the task in question carries risks that justify their direct involvement, and whether the potential cost of delay or error exceeds the value of developing others through the delegation process.

Season over Standard

The final principle concerns duration. The danger of micromanagement is not its existence, but its persistence. When it becomes the standard operating mode of a leader, it restricts organisational maturity. It creates dependency, reduces scalability, and often results in high staff attrition. Over time, it limits the company’s ability to function independently of its founder.

Elon Musk provides a useful case study. His capacity for extreme output and attention to detail has driven extraordinary innovation across multiple companies. However, as Shaw notes, this intensity also creates volatility. Teams may become reliant on his presence, and the cultural atmosphere may also suffer as a result. The leader remains indispensable, but at significant organisational cost.

Micromanagement is best understood as a seasonal intervention. It is appropriate during moments of inflection, when standards are being set, when products are being defined, or when execution is closely tied to brand reputation. Beyond that, the leader must evolve. Precision gives way to structure. Involvement gives way to enablement.

In Summary

Micromanagement should not be romanticised. Nor should it be reflexively condemned. It is a leadership behaviour that, when applied selectively and with clear intent, can preserve quality, protect strategic outcomes, and set cultural tone.

In situations where the stakes are high, where the product is formative, and where the organisation is still learning how to express its identity, micromanagement can serve as a necessary discipline.

It is not an ideal. It is a tool, and like any tool, its value depends on when and how it is used.

Grit isn’t born in crisis. It’s developed through deliberate exposure to challenge. This article explores how professionals can cultivate endurance before it’s needed, drawing on cognitive science and real-world application.